The nocturnal phenomenon, according to rumor, usually occurs right around this time of the year, but some people have reported it as early as September and as late as November. Some describe it as a subtle drumming, a percussive tapping on empty streets and sidewalks, softer than the sound of falling acorns, barely audible in the dead of the night. This faint polyrhythmic drumming is sometimes accompanied by other intriguing sounds—witnesses have claimed to hear the echoes of laughter in the air and the crackling of bonfires whose glow no one can see. On the soft ground of brownstone yards, on formerly busy docks along the East River, on the leaf-covered floor of empty basketball courts, on cobblestone and asphalt, on the meanders of solitary paths that wind around project buildings, and on the roof of old churches—the eerie sounds have been heard everywhere in Brooklyn. Where do these vague sounds that waft through the slumbering streets of our town come from? Who are these invisible presences that laugh and rejoice in empty playgrounds and dark alleys at such wicked hours of the night?

To date, no one has been able to confirm these reports. For all you know, I’m just making them up. But I am pretty sure that a few of the oldest residents of our city could easily identify the source of these phantasmal reverberations that bounce inside my head. The imaginary sounds would probably be an actual memory for them. They are the acoustic shadows of a long gone din that could be heard in the harvest season from Maine to the Gulf of Mexico and from the Applachians to the Atlantic shoreline, a celebratory commotion that announced the arrival of America’s true manna—the cherished chestnuts of the nearly extinct Castanea dentata.

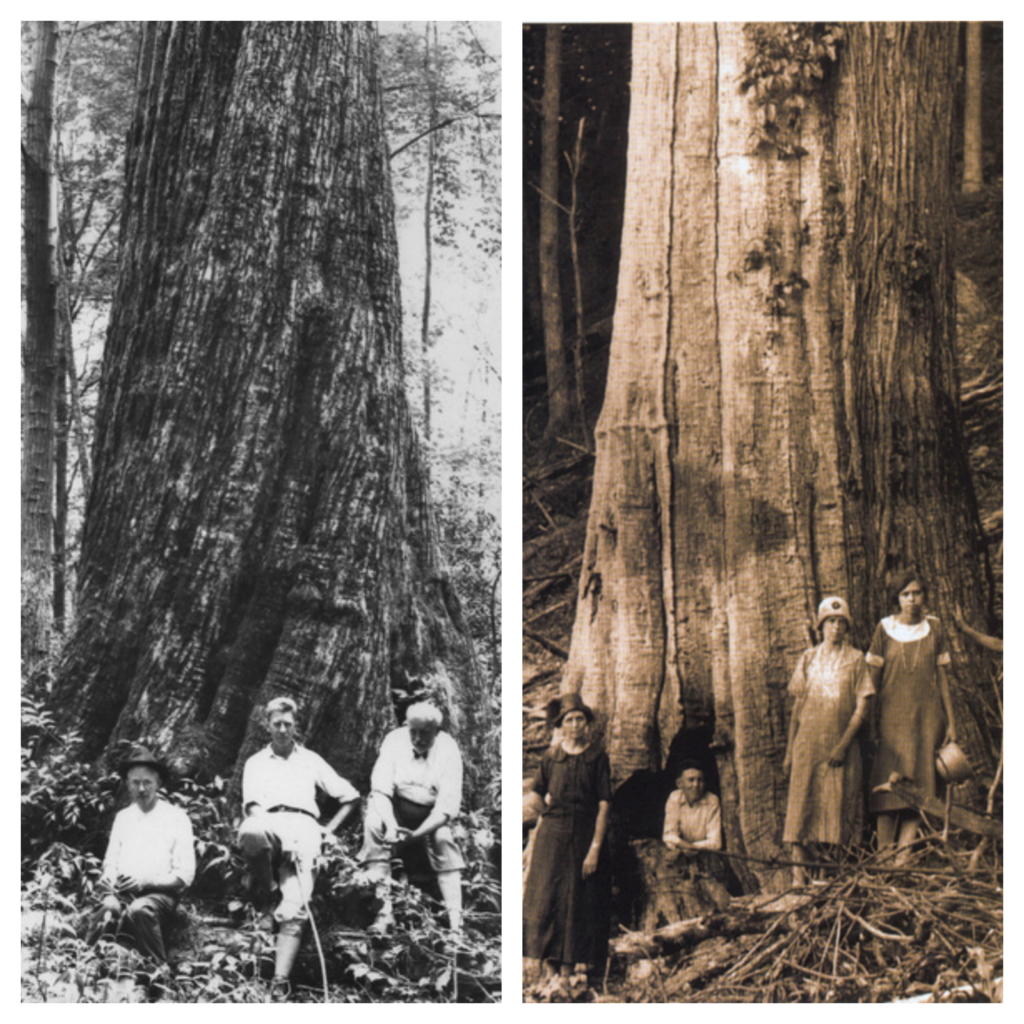

“Here it is, the fabled free banquet of America—yet one more windfall on a country that takes even its scraps right from God’s table.” The sentence is from the first chapter of Richard Powers’ The Overstory. “Now is the time for chestnuts,” states the opening line before going on to describe the joy and excitement that the falling chestnuts spread through the eastern states of the expanding country. The dazzling fictional work draws from factual accounts. Many oral and written records dating from before the first half of the twentieth century praise the abundance of the annual chestnut harvest and the unmatched quality of the American nuts, which are smaller and, according to many, sweeter than their European and Asian relatives. Old pictures show the size and girth of some of these bountiful trees, true forest giants often reaching up to 75 feet, and sometimes well above that. They really must have been a sight to behold. Nowadays these colossus can only be found in old pictures—of the 4 billion American chestnuts that once grew in the Eastern United States, only about a hundred survive today in its natural range. Just a hundred trees of a once dominant species survive in a two hundred million acre territory.

Deadly Spores

Herman Merkel, a forester at the New York Zoological Garden—as the Bronx Zoo was known then—was the first to observe the disease: orange spots appeared on the bark of an American chestnut whose leaves started drying and falling in midsummer. The following year, in 1905, the culprit was identified when mycologist William Murrill isolated the lethal fungus. By then the disease had spread throughout the entire borough, a fact that Richard Powers also relates in The Overstory: “Within a year, orange spots fleck chestnuts throughout the Bronx—the fruiting bodies of a parasite that has already killed its hosts.” Soon all the chestnuts in New York City were falling victim to the disease, which became known as the blight.

In 1912, American botanists Haven Metcalf and James Franklin Collin deduced that Cryphonectria parasitica (originally named Diaporthe parasitica by Murril) sneaked into the U.S. as a host of Japanese chestnut trees first imported from Japan in 1876. The inclusion of the species in catalogues of many American mail-order nurseries only seemed to reinforce their conclusion. Later that same decade, chestnuts from mountainous region of China and Japan were found to host the fungus, thus confirming their hypothesis. Never having dealt with this fungal parasite before, the mighty American chestnut hadn’t developed any resistance to the disease that the Asian trees seem able to withstand. One after another, the North American trees succumbed hopelessly all over their area of distribution as the deadly spores proliferated and colonized every inch of eastern forest over the next decades. It spread through New England and Pennsylvania, defeating all human efforts to stop its advance. Then it took over Virginia and from there moved on unchallenged to the forests of the south through the Appalachian system. By the 1940s the American chestnut was virtually gone—a 40 million year hegemony was destroyed in the blink of an eye as the unforgivable blight cankers strangulated an estimated 25% percent of all the trees in the Appalachian. In less than half a century America’s true manna was no more.

Few ghost stories are as sad as the stories the pale branches of dead chestnuts inscribe in the landscape above the canopies as the sway in the wind. Described as “tall silver white skeletons that tower against the living forest” in this video from the American Chestnut Foundation website, they tell about the deep trail of devastation left by the blight in its conquering march across the Eastern Seaboard: at least three entire insect species gone forever, others drastically affected by the disappearance of their main source of food and shelter, whole industries and ways of life vanished for good; tastes and sights relegated to the realm of memories and primary sources.

The most tragic aspect of the blight, defined by some as “the greatest ecological disaster to strike the world’s forest in all of history,” is our role—as unintentional as it might have been—in introducing the fungus to the American forests and helping it proliferate through actions originally thought to stop its hasty spread. Powerspraying “Bordeaux mixture,” a blend of lime, salt, and copper sulfate used to treat fungus in grapevines, never worked—the mix didn’t reach the fungus below the bark. Cutting affected limbs and trees only helped to disseminate the spores in the environment, while the preventive felling of healthy individuals accelerated the destruction, possibly killing any specimens that might have proven resistant to the blight.

Yes: we did start it all and then made it worse. But not all is lost. We are a wreckless species, but we are also clever, and maybe just clever enough to pull the American chestnut out of functional extinction.

Brought Back from the Dead

One particularity of the blight is that it doesn’t always kill the roots of the chestnuts when it attacks. Only the stem tissue above the cankers, deprived of water and nutrients, dies. In fact, living root systems in Appalachia still shoot new branches toward the sunlight in the depths of the forest, but they inevitably die before reaching maturity, which for chestnuts occur past seven or eight years of age. While the trees are gone, the roots survive, and so does the relenteles Cryphonectria parasitica. In order for American chestnuts to come back from the limbo of functional extinction and take back their place in our forests and parks, a resistant Castanea dentata must first be developed.

Starting as early as the 1920s, different initiatives, publicly and privately funded, have tried to do just that, experimenting with different crossing methods in order to revitalize the species. The first efforts, led by the Brooklyn Botanic Garden and USDA, tried intercrossing American chestnuts with a blight resistant Asian chestnut, but the results were not good enough to continue the programs past the 1960s. With the creation of the American Chestnut Foundation two decades later, different teams of foresters and geneticists started backcrossing hybrid chestnuts into American chestnuts, but the results have shown partial success, with some trees developing a limited resistance to the disease. Genetic engineering programs designed to enhance and speed the results of the American chestnut hybridization programs offered a new hope starting in the 1990’s. By 2012, Science News announced the planting of ten transgenic trees developed by SUNY’s College of Environmental Science & Forestry in collaboration with the American Chestnut Association in the Bronx, not far from where the orange spots of the blight were first discovered. Transgenic hybridized trees are still growing today in several experimental plantations, but we now know the process will take longer than many had anticipated.

Hybridization is not the only approach. European chestnuts were saved by a type of virus that attacks Cryphonectria parasitica, weakening its devastating effects and slowing its reproduction, thus giving trees a chance to develop their own resistance to the disease. This type of virus—known as hypovirus—has shown its effectiveness in slowing down the progress of the disease in American individuals, but due to its slow spreading rate, it can’t yet compete with the healthy lethal fungi that still live in our forests. Work is in progress, but finding strains of both virus and fungus able to proliferate as effectively here as they did in European woods hasn’t yet been achieved.

Not one single method can yet claim success. Perhaps a combination of all these approaches will one day yield the desired results, but we still have a long way to go. It is hard to be optimistic in the face of an environmental policy that seems deliberately designed to strip forests and other natural areas of protections that have been in place for years, barely holding against our insatiable appetite for land and resources. Only time will tell if there is a real chance for Castanea dentata to thrive once again in shrinking forests with a much higher population of hungry deer than it had a hundred years ago.

There are things we can do. We can donate to organizations like the American Chestnut Foundation and learn more about other practical ways in which we can be part of the recovery effort. We can also set our priorities in place and vote at every level against any policy that threatens to accelerate the destructive effects of human activity on the environment. Will we ever see American chestnuts growing in places that bear its name? Will we ever hear and see their sweet husked seeds raining on the countless Chestnut streets, avenues, parks, and towns one can find across the United States? Surely in our collective memory and in our dreams for a better future, but probably not in our lifetime.