by Emily C. Shue

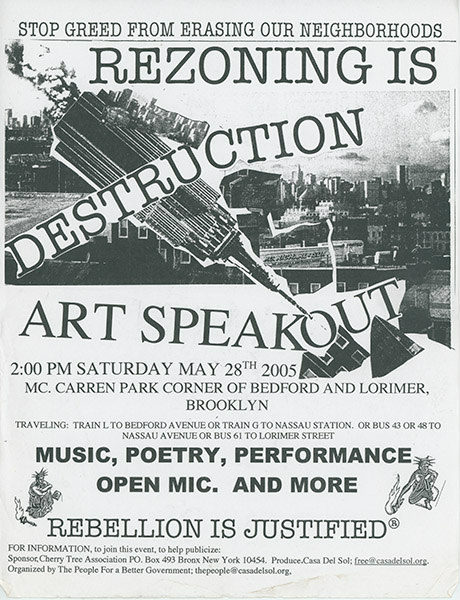

“REBELLION IS JUSTIFIED,” reads one flyer. In the bottom corner, a small graphic of the Statue of Liberty throws down her torch in protest. It was an event flyer for Art Speak Out for “an afternoon of music, poetry, performance, open mic, and more,” protesting the historic waterfront rezoning in Williamsburg and Greenpoint in April 2005. The Department of City Planning and City Council successfully passed the rezoning in May 2005, although they did make a few concessions to the neighborhood activists. Community planning needs were included but not prioritized, and there were “no significant concessions” on the City’s part.

Stories like this were represented in abundance at the Brooklyn Public Library’s (BPL) Greenpoint Environmental History Project Reception and Exhibit. On Thursday, June 20th, the Amalgamated Drawing Office, or A/D/O, showcased a fascinating history of official documents, planning, flyers, home-made posters, signs, and oral histories. Made possible by the Greenpoint Community Environmental Fund, or GCEF, The Greenpoint Environmental History Project documents different eras of activism and shows the growth of different community organizations in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, two dynamic neighborhoods in New York that have seen decades of rapid change and growth.

GCEF was founded in 2011 with funding from the State of New York in a settlement with ExxonMobil over the Greenpoint oil spill. One GCEF grant allowed Acacia Thompson, Brooklyn Public Library’s Greenpoint Outreach Archivist, to meet with members of the Greenpoint and Williamsburg communities and gather their stories. Thompson was able to interview activists who participated in protests, lead coalitions, and who have lived in the Greenpoint and Williamsburg neighborhoods for decades. All of the materials are available to explore in the Brooklyn Public Library’s digital collections.

“Environmental equity has always been [a concern] in this neighborhood,” said Ames O’Neill, BPL’s Office of Strategic Planning’s Project Manager. “She did an amazing job. All of the oral histories were digitally recorded and have been uploaded onto Soundcloud, and everything… is captured digitally and is available on our website. Anytime, anywhere!”

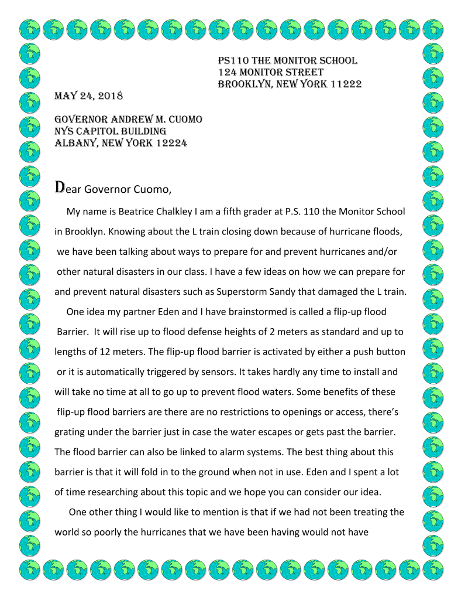

One of the collection’s more recent pieces is a letter from fifth grader Beatrice Chalkley to Governor Andrew M. Cuomo. “I am a fifth grader at P.S. 110 the Monitor School in Brooklyn,” she writes. “Knowing about the L train closing down because of hurricane floods,we have been talking about ways to prepare for and prevent hurricanes and/or other natural disasters in our class.” The collection has examples of public correspondence dating from the early 1990s to Chalkley’s letter in 2018. Other materials included in the collection include maps, photographs, newsletters, reports, and more.

Thompson enjoyed her work with members of the Greenpoint community. “I feel so fortunate that I got to hear these stories and now everyone gets to hear them as well.”

One of the documents on display at Thursday’s exhibition was a final report from the Newtown Creek Alliance, one of many community organizations highlighted through the project. “Creek Speak” details the history of the oil spill’s effects on Newtown Creek, which “has seen a number of rediscoveries” spanning from 1950, when a “large underground oil spill” took place to 1978, when the Coast Guard “detected signs of an oil spill entering Newtown Creek,” to the 2000s. The most significant discovery took place in 2002, and saw true action. Basil Seggos, one of the chief investigators of a local organization “determined to defend the Hudson River and its tributaries” was “stunned… [by the] horrible contamination along the Newton Creek.” Seggos helped to found the Newtown Creek Alliance and lead the movement to clean up the mess plaguing their community.

The edition of Creek Speak on display detailed their Community Health & Harms Narrative Project (CHHNP). NCA interviewed residents about gentrification, past and present problems with pollution, connections between the environment and health, concerns about awareness, whether or not citizens thought the city or government was to blame, and what could be done. All individuals were over 18 and had lived in the area for over five years. Answers varied. Many residents were saddened by the changes over the years. It’s true that Greenpoint and Williamsburg are the most gentrified areas in New York City. The CHHNP noted that “ongoing gentrification has tended to push out long-term residents who can no longer afford to live in these communities, breaking social ties.” The industrial growth and pollution were a concern among residents, and there was a consensus that the area was polluted.

Despite the pollution being common knowledge, there was noted excess of misinformation. Residents receive their news via “word of mouth,” and were more often than not “unclear on specifics,” especially surrounding remediation, historical timeline, and the original spill itself. Participants were divided on the connections between the environment and health, on who to blame, and on how to move forward. Some believed that responsibility rested solely with the individual, while others were adamant that only a community effort would produce results.

In truth, for over 140 years, over 17 to 30 million gallons of oil leaked into the Greenpoint community.While remediation and reparations were initially set up, they were disproportionately small and did little to offset the damage. According to the NCA homepage, Mobil “add[ed] insult to injury” by spilling “an additional 50,000 gallons on oil into Newtown Creek and Greenpoint during one winter week in 1990.” Continued delaying tactics and failure to adequately address the disaster lead to community action, and the resulting settlement allows GCEF to fund many community projects.

The next big project is the new Greenpoint Library and Environmental Education Center, scheduled to open in Fall 2019. “We were able to totally rebuild it,” says O’Neill. “It’ll be twice as big as the old library.” The new building will stand at the existing site of the old branch at two stories tall. O’Neill lists all the green features excitedly. “[It will have] a garden, solar panels, bio-soil, rainwater harvesting…” The Brooklyn Public Library website claims the new Greenpoint Library and Environmental Education Center will be “a model of sustainable development” that will “exceed LEED Green Gold Standard Building Requirements.”

The U.S Green Building Council (USGBC) developed Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), a national certification system to encourage building green, eco-friendly and energy-efficient buildings. The rating system is complex and unique compared to other rating systems, specifically because it is conducted by third party experts who document all construction techniques and material selections throughout the building process. The Gold standard requires a building to accumulate 75 points based on various categories including site sustainability, materials and resources used in construction, and water efficiency.

Thursday, however, O’Neill revealed that they will be aiming for Platinum standards. Platinum bumps the point accumulation up to 90 and requires builders to meet even stricter standards of eco-consciousness.

To celebrate the on-going march towards green living, the Brooklyn Public Library is holding the Green Series. The Green Series “explores topics related to the environment and sustainability, with author talks and discussion panels for adults, plus interactive programs for kids.”

You can sign up for project updates on the Greenpoint Library and Environmental Education Center here. Be sure to explore the Greenpoint Environmental History Project digital archives and oral histories!