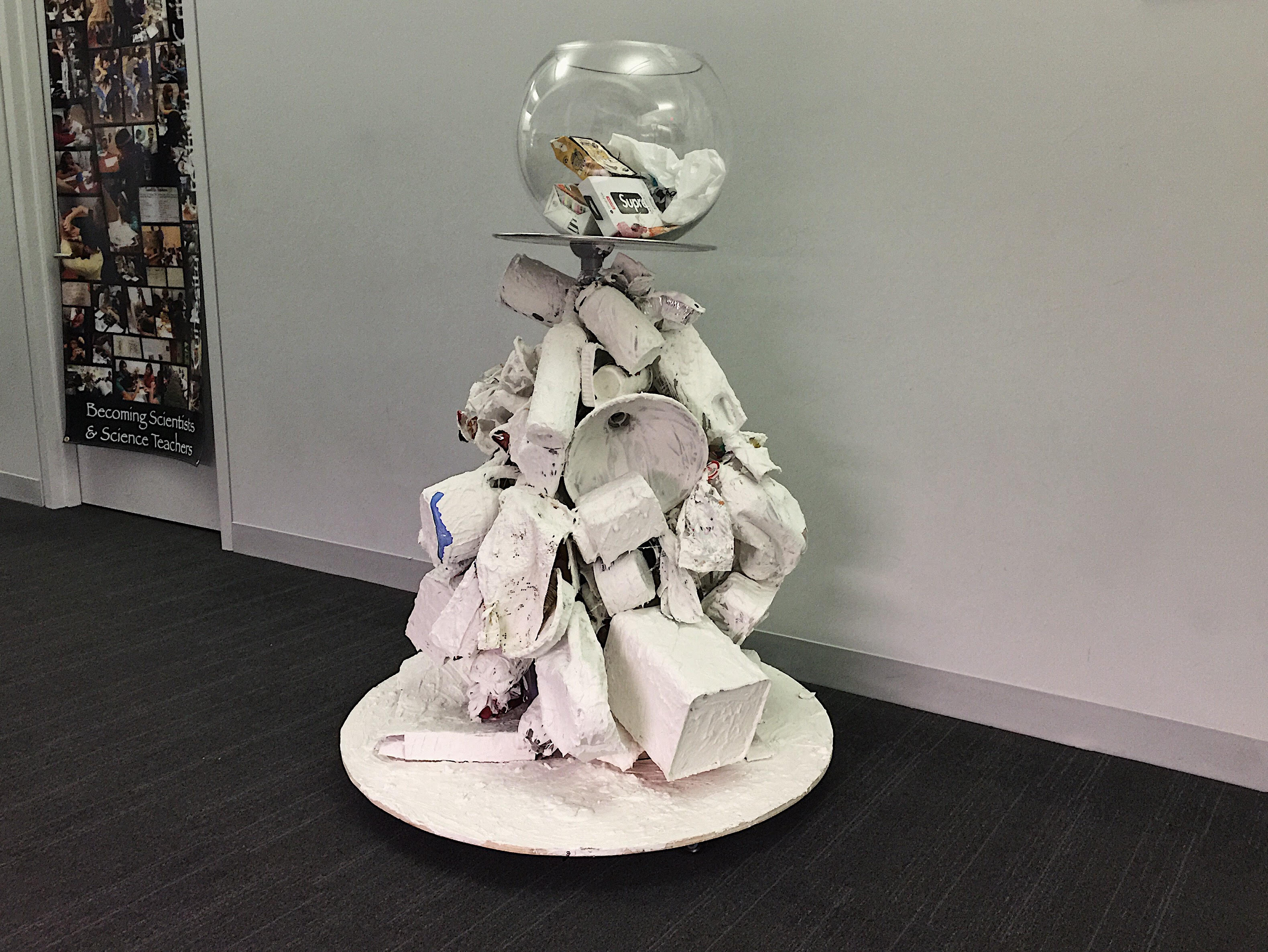

Article and sculpture by Yinan Lu, artist and Master of Arts Candidate at New York University. Lu created a sculpture made entirely out of trash and recyclable material, “The Ghost of Consumption.” Read about her work and inspiration below.

* * *

The Ghost of Consumption

Artist: Yinan Lu

NYU MA Candidate in Environmental Conservation Education Program (2019)

Marcos Solari NYU/ITP (2003)

Material: Garbage, Metal, Wood, Plaster, Glass

“When will you look at yourself through the grave?”

‘America’ Allen Ginsberg

We pay visits to graveyards, cemeteries, and mausoleums; to mourn and to remind ourselves how the past could influence the present and the future. ‘The Ghost of Consumption’ brings the graveyard of consumption goods from marginal places into a topic of public debate. When a viewer’s gaze fixates on the crumbling pile, the viewer is facing our ready-to-waste consumerism culture: a look into a momentum of our own doing. The artists hold up a mirror, to reflect a burial ground from crunchy food wraps and cotton swabs. The purpose of this piece is to raise awareness of our problematic waste issues and encourage individuals to question how one could participate and bring about social change: move away from destructive consumption towards a circular economy.

* * *

In nature, the concept of waste does not exist, everything in the biological cycles is made to compose and decompose; materials used and discarded by one organism would have become the resource for other living organisms. Until the advent of the industrial revolution, “material shortage was the norm, discarding things is a notorious way of demonstrating power.” (Strasser, 1999, p.9) For goods that came to the very end of their life, historically humans bury them. When we look at the waste stream as near as 150 years ago, it consisted mainly natural material: paper, wood products, animal byproducts, and natural fabrics. These wastes would decompose and not cause long-term environmental consequences.

Industrialization, in its eternal quest to mass-produce more at a lower cost, introduced product types that began to alter these waste consequences. More so, it kicked off a one-way system where natural resources are constantly extracted from earth, converted into consumer goods and byproducts, sold and once consumed, disposed into the ecosystem by way of landfills, incinerators and unregulated dumping grounds. The rapid increase of supply and demand of such mass-produced consumer goods is not only resulting in staggering waste levels, but also introducing toxicity to the waste stream with products composed of metal, acid, radioactive and synthetic plastic materials.

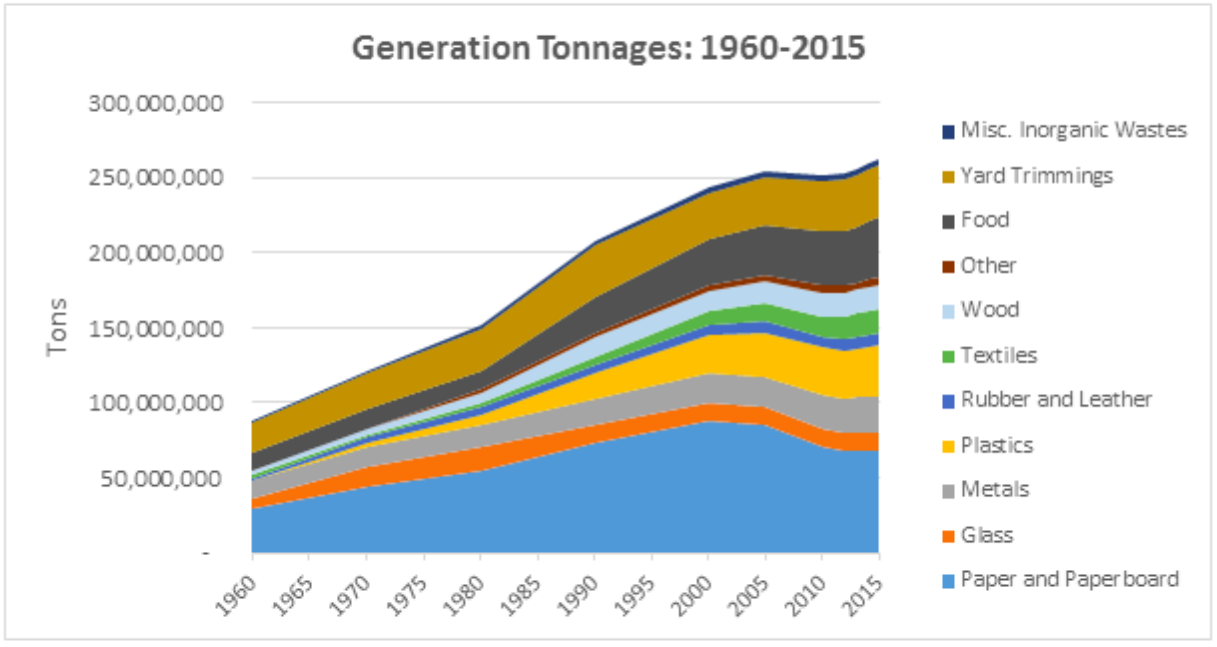

This rapid increase of waste can be seen clearly in recent waste statistics captured. The amount of waste produced and disposed in the US went up 150% from 100 MM tons of trash disposed in 1960 to 250 MM tons in 2015. By 2015, the average amount of waste produced per person in the US totaled 4.4 pounds of trash a day.

Disposing such amounts of trash daily creates more than environmental problem, it has direct impact as a social issue: when trash is taken out from households to the curb or from a person’s hand to a city trash bin, the trash itself becomes a public matter, a problem to be solved through the public policies of cities and counties on how and where that trash is to be managed. However, the visibility and transparency of such policies are blurred up with each garbage truck that hauls waste away, creating an out of sight, out of mind, not in my backyard phenomena that makes us not want to really know where the stuff ends up.

Society has not addressed this matter as problematic. On the contrary, it values consumption and the hidden resulting waste levels, instead of educating society on the environmental consequences that these values produce. The results of these consumption values are visible when we look around us. According to Humes: “We are wasting so much stuff every day that trash has become a geographic feature —- particles transforming oceans, garbage mountains dominating landscapes, a landfill visible even from space” (Humes, 2013).

Landfills and incinerators in less developed urban areas are invisible to all but the poor. When waste management systems become overwhelmed, or legislation against toxic dumping breaks the status quo, the system exports its waste to underdeveloped countries in order to create more sites for landfills, incinerators, and uncontrolled dumpsites deteriorating the lives of those exposed to those new sites. While most of the world is lucky enough to live free of these conditions, no one can escape from a much bigger invisible problem with a greater dimension—our impact on the environment with our consumption habits. The ghost of consumption that’s wandering in the air, water and soil will eventually haunt our earth.

Graph 1 shows two categories of waste (food and plastic) and the dramatic increase they underwent over a 55 year period: Food waste is responsible for substantial amounts of methane emissions. Even though food waste eventually decomposes, they presently clog up in landfills.

The first use of synthetic plastic appeared in the early 20th century, but large-scale production and its use did not take off until the 1950s. (Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R., & Law, K. L. , 2017). Since 1950, 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic have been generated. Of this amount, only 2.5 billion metric tons are currently in use, with the remaining 5.8 billion metric tons in landfills.

Mass-market products promote consumption of goods that are “devised to be thrown out after brief use: packaging designed to move goods one way from factories to consumers, and “disposable” products, used one time to save the labor of washing or refilling… goods obsolete owing to changing tastes.” (Strasser, 1999, p.4). After the turn of the twentieth century, plastics’ largest market is packaging, in the book ‘Gone Tomorrow’, Rogers states that “packaging comprises the single largest category of household waste, taking up 30% of all landfill space in the U.S.” (Rogers, 2006). Plastic bags are used for an average of 12 minutes. The average time required for plastic to decompose is 500 years to never. In other words, all the plastics ever produced still exist in our world in unrecognizable forms, accumulating in landfills and the natural environment.

Food and plastic waste is also only the tip of the iceberg. Fossil fuels and chemicals are also big contributors which, when decomposing, leach toxic substances into the soil and water. “The rate of climate change is perhaps the broadest barometer of environmental health and is closely linked to trash; the more that gets thrown out, the more pollution-causing processes are relied on to make replacement goods.” (Rogers, 2006, p7)

If markets and the economy are driven by consumers and their behavior, can we strike the top-down power structure of consumerism by reviewing and revising our consumption behavior? As individuals in a society, are we so powerless that all we can do is shrug our shoulders and pout? When we make a purchase decision for something considered ‘convenient’ or something that enables time-efficiency, are we really thinking about the impact these decisions have long term? Beyond basic needs, most of the things we think we want or need are likely an illusion caused by aggressive marketing campaigns, persuading us to become members of this endless mass consumption bubble.

Numerous global goals aimed at sustainable development are finally allowing us to begin practicing what we have been preaching all along: to change our production and consumption patterns to create virtuous cycles. We live in an anthropocentric culture that places human beings at the center of it all, making everything else revolve around them. When we take a step back and look at our civilization, it is clear that humans live in and rely on only a part of the environment. Let’s envision a society that will move away from the current consumption model to a circular economy: a regenerative long lasting system that minimizes resource input and waste, promotes maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing and refurbishing, recycles and upcycles.

References:

- Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R., & Law, K. L. (2017, July 01). Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Retrieved from http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/3/7/e1700782.full

- Humes, Edward. (2013). Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair with Trash. New York: AVERY.

- Rogers, Heather. (2006). Gone Tomorrow: The Hidden Life of Garbage. New York: The New Press.

- Strasser, Susan. (1999). Wast and Want: A Social History of Trash. New York: Holt Paperbacks.